It's thought that only 7% of what we communicate to others is by words. A staggering 93% comes through body language – the ‘silent language.’ In drama and communication, our body language is crucial, especially in the development of characters.

This one-off workshop explores some ways the body communicates meaning, develops characters, and obliges students to collaborate and work together to produce a dramatic outcome.

Objectives:

- To collaborate on devising a piece of drama using body language

- To explore physical drama techniques to convey meaning

- To utilise a range of drama techniques to develop characterisation

Materials, resources and research:

‘Is That Your Body, Boy?’ is the title of a play in the BBC Thirty Minute Theatre series. Broadcast in 1970, it centred round a vicious physical education teacher who used the insulting, sarcastic phrase to humiliate hapless pubescent pupils who were less than fit or slim enough for his approval.

As IMDB puts it: ‘The weedy kid being ridiculed is a regular staple of conflict drama, where he/she fights back or not. It suggests crowd behaviour, bullying, physical and gender stereotyping – all of which resonate today.’

Resources:

-

Body Language: 7 Easy Lessons to Master the Silent Language (2009) by James Borg (Ft Press)

-

Healthline, A Beginner's Guide to Reading Body Languagewww.healthline.com/health/body-language

-

Science of People, 16 Essential Body Language Examples and Their Meaningswww.scienceofpeople.com/body-language-examples

Warm-ups: (15 mins)

A. Solos: Ask students to mime the following – scratching their nose absently, scratching their ear after an insect bite, avoiding the gaze of a friend, using arms to show rejection, miming an angry speech.

B. In pairs, mime entering a dark building without making noise or being seen. C. In pairs, repeat with comic exaggeration. D. Groups of 4/5, mime a café with one server and customers, ordering, drinking alcohol, food arriving, some sent back, anger, arguing, leaving the café.

Teacher-led discussion (5 mins)

Discuss the body language we use a) ordinarily and b) when we're agitated, nervous, desperate or fearful. Do students have examples?

Drama is about communicating meaning to others, so physicality and mime are essential. We're not robots.

Experiment with body language (10 mins)

Ask students in pairs to experiment, with mirrors if you have them, or use a partner as a mirror, stretching what every gesture could mean.

- Language of the face – mouth, eyes, teeth, hair, chin

- Language of the limbs – arms, hands, legs, fingers, whole head, shoulders

- Language of whole body – sitting, crouching, kneeling, standing still, standing and fidgeting, back to audience, facing audience, dancing

- Language of body combinations – hand to face, both arms, arm and leg, head and hand.

Mimes for the character (5 mins)

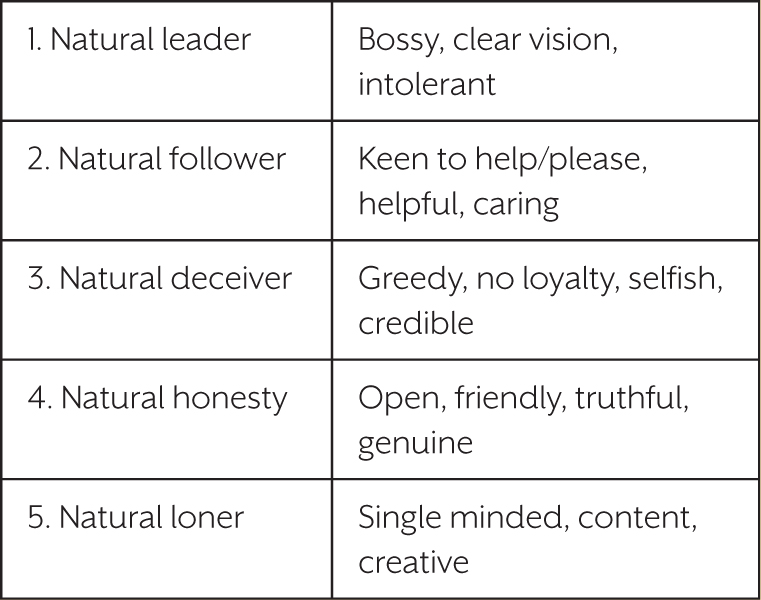

Ask students in groups to create a series of mimes to fit the character they'll play in a group of teenage friends.

Borrowing Laban movement:

Initially concerned with dance, the Eight E~ orts: Laban Movement (www.theatrefolk.com) Laban lessons develop the physicality of characters. In their characters, have students walk solo in the drama space with the following instructions –

- direction, go directly to something, or wander vaguely towards it

- weight, how heavy/light is the character when moving?

- speed, how fast does he/she go, are they sustained or hesitant?

- flow, is body tense or does it move freely? This one depends on the direction/purpose of the walk.

Eight Efforts: Laban's eight efforts in movement are: wring, press, flick, dab, glide, float, punch, slash. Invite students to explore these terms.

Devising:

Students must make one short scene where teenage friends, in the characters already started, are preparing, cooking, eating and clearing up a simple meal. Every emotion, thought, feeling must be through body language. Only one short sentence may be spoken by one character. Limit speaking. Masks make physicality more important, though how the body language is seen by others is determined by the design of the mask.

Sharing and showing so far:

Invite each or selected groups to share progress to date. Check that physicality conveys meaning.

Reviews and learning summary:

- Allow time for quick self-review, positive peer review, and teacher review: comment and advice forms part of learning.

- Use reviews to summarise learning on movement and physicality.

Following up:

Further work on Laban movement, mime, masks, and physicality to convey meaning will improve individual approaches to characters.