Producing excellence

Nick Smurthwaite

Sunday, March 1, 2020

Nick Smurthwaite finds out what it's like to work as a theatre producer and how students who'd like experience in the role can get started

HOLLY WREN

Being a successful producer requires a wide range of skills and attributes, from an ability to inspire others to a gambler's certainty that the horse you've backed will gallop home to victory.

In the commercial sector it is the producer's primary duty to ensure that a show's investors get a return on their money. To do this, they must convince them that the show is a sure-fire winner. Then the producer has to go away and come up with the goods. It is often a lengthy and stressful process.

How can you become a producer?

To say producing is not an exact science is a massive understatement. Sonia Friedman, by far the West End's most successful commercial producer of the past ten years, says her secret weapon is a kind of fearlessness, or ‘that thing you have when you're young of not knowing what's impossible.’

Friedman cut her theatrical teeth in the subsidised sector, first as a stage manager and rookie producer at the National Theatre, then as co-founder of the touring company, Out of Joint.

She knew next to nothing of the processes of commercial theatre when she set up her own company in 2002. She says, ‘I made some catastrophic choices including one show that played to 17 people a night. I was totally at sea.’

Because it's such a precarious occupation it has been said that producers are born rather than made. In other words, it's their destiny. If you talk to any successful producer, they've invariably shown signs of entrepreneurial zeal at an early age.

Cameron Mackintosh says he knew he wanted to be a producer at the age of eight when his aunt took him to see the musical Salad Days. By the time he was in his teens he was working as a stagehand at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, the venue he was later to occupy with triumphant productions such as Miss Saigon, My Fair Lady and Oliver!

David Ian (Grease, Saturday Night Fever) gave up a promising career as a musical theatre performer to go into partnership with the actor Paul Nicholas in the 1990s to produce a revival of Jesus Christ Superstar and hasn't looked back since.

Unlike designated backstage disciplines such as stage manager and company manager, there doesn't seem to be a specific training path for producers – you learn it by doing it – however there is an excellent charity called Stage One which supports and instructs rookie producers with workshops, networks and investment schemes.

Production manager vs. stage manager

If the producer is in charge of a show, the production manager is the second in command, doing the day-to-day work on the ground and making sure everything runs like clockwork. Again, it is a designation that's best learnt by doing.

On a big touring musical, the production manager must ensure that everything is ready at each venue to accommodate the needs of the show, from the backstage rigging to the front of house publicity. So, there is a lot of multi-tasking and forward planning needed, as well as expert communication skills. How production managers ever managed before the invention of the mobile phone is a mystery.

Chris Boone, production manager of the UK tour of Les Misérables, did a lot of other backstage jobs – followspot operator, master carpenter, stage crew – before he became a deputy production manager on Mary Poppins in 2005.

© ROYAL OPERA HOUSE

The ABTT offer Bronze, Silver and Gold awards for theatre technicians and electricians alongside CPD courses

Organising a huge show like Les Misérables is tantamount to leading a military campaign. Not only does Boone have to arrange for the transportation of 80 tons of equipment from city to city, but he also has to liaise with different teams of manual workers at each venue in addition to his own permanent staff and the in-house staff at each venue.

He is also required to stay calm through every crisis and make sure all departments have the right information at every stage of the operation. ‘We only need one link in the chain not to work and we are screwed,’ says Boon, ‘It's all down to careful planning and communication.’

On a smaller-scale production, say a fringe show in a fixed venue, the producer sometimes shares what would normally be the production manager's duties with the stage manager, provided the logistics of the show are uncomplicated and the creative team small.

As with many stage endeavours, you have to be prepared to be flexible, do whatever is required with the resources available, and work long hours for little money.

The stage manager is a key figure in any stage production of any size. It is their job to ensure the smooth-running of each performance, which requires seeing everything is in the right place prior to the curtain up, including the actors, and then co-ordinating all the technical aspects of the show, principally lighting and sound.

The bigger the show, the larger the backstage team. Most musicals have a deputy stage manager, a production manager and at least one assistant stage manager, all with separate and specific roles in the running of the show.

Most stage managers are formally trained in all the backstage disciplines so that, when they finally land a job, they know exactly what everyone does, why and when they do it.

Getting the right experience

13 of the 20 schools that make up the Federation of Drama Schools teach technical theatre and stage management, often under a generic label such as Production Arts.

These courses are approved by the Stage Management Association, as are those in a handful of universities, so there is a clear understanding that they offer vocational and practical training that equips students to become employable stage managers, costume makers and so on.

There are other non-academic routes into the industry. Many backstage and production careers have sprung from work experience or volunteering. Nearly all regional theatres use volunteers for front of house and ushering duties. So, if you are in easy reach of a regional venue it is always worth finding out if they need casual staff.

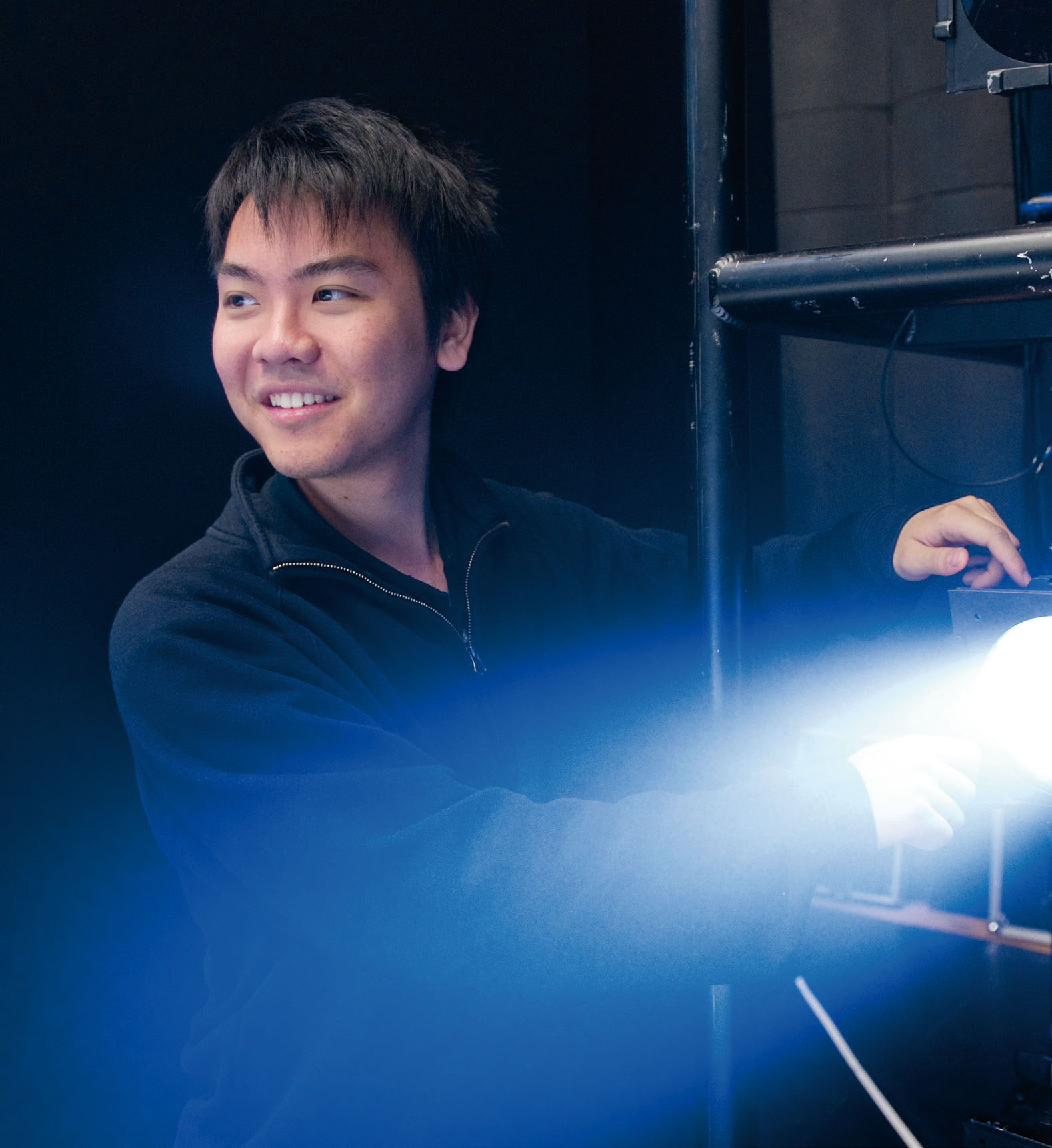

Chris Davis learnt the ropes by assisting the full-time technicians at Exeter's Northcott Theatre. He says, ‘the most important thing is to have the right attitude and never be afraid to ask questions.’

According to Kate Ferris, head of stage management at Dublin's Lir Academy, ‘good communication is the key to excellent stage management.’

She says, ‘If you don't know how to listen, disseminate information in a clear and coherent way, and then trouble-shoot while keeping calm and acting like a true leader, management of any kind is not for you.’

Ferris also cautions, ‘Hours are long and sometimes it feels like you haven't seen the daylight in weeks. Getting a good work/life balance can be tricky in any live performance job.’

She believes the one skill every successful theatre professional needs is ‘the ability to nurture relationships, build partnerships, trust your colleagues and look after the people you're responsible for.’

Ian Evans, head of stage management and technical theatre at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, says, ‘If you want to progress in this industry you must have the right attitude, top communication skills and application. If you have all three, people will help you up the ladder even when you have to learn a new skill on the job.’