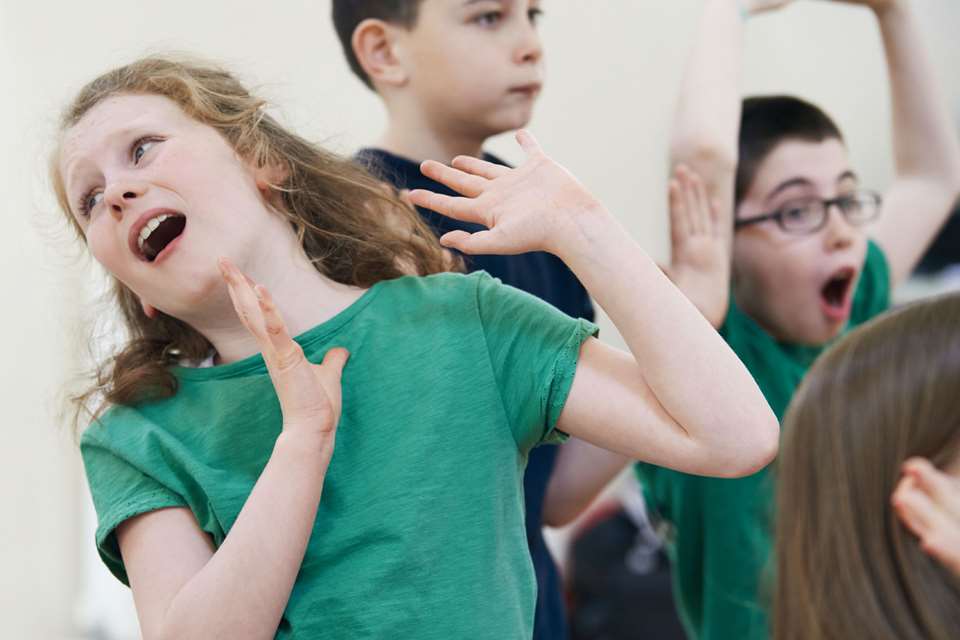

Drama strategy: Teaching PSHE through drama

Patrice Baldwin

Friday, October 1, 2021

The PSHE curriculum is intended to help students manage their lives, stay healthy and safe, and prepare for life and work. Drama can provide shared, imagined contexts and experiences, within which real life situations can be explored meaningfully, with whole classes.

Adobe Stock / ONYXprj

The students stay safely distanced on a personal and emotional level, as they are ‘working in role’, within a fiction. The PSHE knowledge gained, and the skills practised, are often highly memorable and help them in their real lives and within future workplaces.

Drama strategies can be used to stimulate and scaffold students' thinking and inter-thinking. Used selectively, sequentially (and hopefully aesthetically), they provide structured opportunities for students to think, talk and act collaboratively, within a PSHE focused drama. Drama is a social activity and provides opportunities for practising teamwork, leadership, perseverance, negotiation, presentation and many other important life and work-related skills.

All drama is story, and all stories have PSHE elements. Teachers can choose relevant picture books and other texts and images, as the basis of a drama. They can then select drama strategies to focus attention on the PSHE elements of the story/drama.

Teachers can pause the drama, invite students to come out of role and reflect together on the actions, reactions, interactions, relationships, problems, dilemmas and challenging situations within the drama. They can then re-enter the drama in role, with the PSHE elements more clearly in mind.

Students may have sensitive, real-life experiences that resonate with the drama but the boundaries between fiction and reality need to be maintained when working in role.

1. Conscience Alley

We speak a character's conflicting thoughts, at a moment of indecision or crisis.

The class stand in two lines facing each other. As the character walks between the lines, each student speaks one of the character's thoughts as he/she passes by. The lines offer opposing viewpoints, which need to be justified, for example:

Character: Her brother keeps hurting her. Should I tell someone?

Line 1: You must tell someone because he will keep hurting her.

Line 2: Mind your own business because it's a family matter.

2. Passing Thoughts

We tell a character what we think about them (and/or their behaviour).

A class circle (standing), with a character in the middle. Anyone can pass by the character and speak a sentence to them, such as: ‘What you posted online was cruel and you've really upset her.’

The instruction can be changed, for example: ‘Pass by and give the character one piece of advice.’

3. Proxemics

We physically position ourselves in relation the character and justify our positioning.

The character stands in the centre. In turn, each student enters, positions themselves and justifies their positioning. Examples include: ‘I am standing away and turning my back because you stole someone's food and that's wrong’ or, ‘I am standing beside you because you were hungry when you took the food.’

4. Thought Walk

Everyone walks around, speaking ‘in role’ thoughts to themselves.

An antisocial or oppressive incident may have been witnessed by them, within the drama, such as vandalism, sexism or racism. They walk around, talking to themselves in role, saying what they think and feel, and maybe what might or should happen next.

5. Freeze-Frame

A scene (improvised or devised) is ‘frozen’, (often at a pivotal moment).

A frozen scene provides thinking time for observing, interpreting and sharing reflections about what is happening. Students can discuss the situation and maybe question it by talking with characters in the scene, for example:

A child is being offered their first cigarette. Freeze…

In drama, they can explain to the student, why he/she needs to refuse the cigarette and can coach him/her in ways of refusing it, (see also Forum Theatre).

6. Forum Theatre

Scenes are devised and replayed in different ways, with characters instructed and directed by the interactive audience (spectators), as to how they might try dealing with the issue or problem differently, for a more positive outcome.

The class watch the scene, for example a bullying incident. The teacher then can operate as an intermediary between the actors and audience. Audience members give various directions to selected actors about how they should speak, act or respond differently when the scene is replayed. For example, instructions such as ‘Stand up straight. Don't look like a victim’ and ‘You go and get a teacher.’ The scene is then replayed differently, and the outcomes evaluated. This process can be repeated.

7. Eavesdropping

We hear in turn, what everyone is saying ‘in role’.

The drama can be frozen, and the teacher passes each student. When the teacher is near, those nearby recommence speaking ‘in role’ and freeze again once the teacher moves on.

8. Mantle of the Expert

The students are usually in role, within imaginary workplaces, with tasks to complete, that require expertise. Tasks have often been commissioned by an imaginary external client, (often the teacher in role). This task can help prepare students for workplaces.