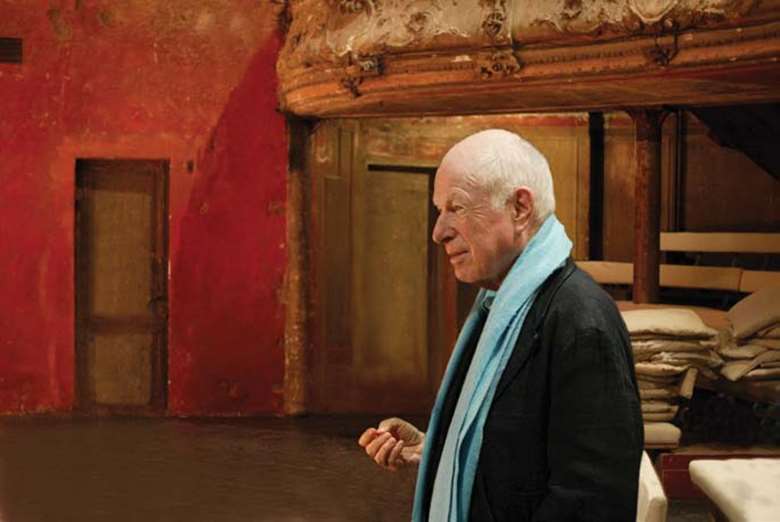

Practitioner focus: Peter Brook – Part two

Peter Jolly

Friday, March 1, 2019

A second visit to the theories and methods of the great 20th Century theatre director

Thomas Rome

Brook's willingness to provoke extends to thoughts on drama theorists, ‘I stayed clear of all theories. I hardly read Stanislvasky or Brecht& I read Artaud& I thought his theories were absolutely useless’. He would not want students to become bogged down in words and theories, but want them to practically explore, examine and act.

Theatrical Journey

Brook's journey took him from ‘using every device known’ on stage to discovering that ‘the human being is richer than the greatest stage effect’. Through putting the human under the microscope Brook unlocked a new exciting world of detail. He believes that ‘acting begins with a tiny inner movement so slight that it is almost completely invisible’, and the director's job is to see the movement and make sense of it for theatrical purpose. This focus has led him to be described as minimalist, yet he firmly rejects this label, ‘I am not a minimalist& I love trying out everything’. His productions have though become increasingly simplified, concentrating on the relationship between the actor, the audience and the playing space.

His view of the director

The director is central to Brook's notion of the creative process and he strongly argues against the idea that directors are unnecessary, ‘without leadership a group cannot reach a coherent result within a given time’. It is the director's job to ‘attack and yield, provoke and withdraw’ and he believes that the director must be in full control in the rehearsal studio. He loves the push and pull between the actor and director that leads to moments of creativity, clarity and discovery. Brook's own notes reveal detailed planning, but he believes that rehearsal should always be fresh, ‘the director who comes knowing what he expects of the actor is a rotten director’. It is helpful to think of Brook as an experimental scientist rather than a ‘traditional’ theatre practitioner.

The Audience and the ‘Present Moment’

Given his view of the director it might seem surprising that Brook says ‘too much time in rehearsal can end by destroying the unique possibility which the third element brings’; the ‘third element’ is an audience. If theatre is to be meaningful then Brook believes an audience should engage with the actors well before the play becomes set in stone. He believes in the ‘present moment’, which he compares to an atom that contains infinite possibilities when it is fractured – this analogy reveals Brook's excitement with the explosive possibilities of live theatre.

Shakespeare

Brook's approach to Shakespeare is to try and shed the weight of cultural expectation: a danger he feels can lead to dreariness. He describes his responses to Shakespeare in his book, The Quality of Mercy, but his shorter Evoking (and forgetting!) Shakespeare is a more punchy and pithy text for the student. He is keen to strip the plays of historic baggage, yet also keen to avoid the actors imposing personal experiences on their roles as they develop in the rehearsal room.

Exercise 1: Shakespeare with Physical Activity

Brook suggests this exercise as way of reinventing text, releasing the word from tired actions. Any piece of text can be selected for experimentation.

- The actor should stand and perform the selected text.

- The actor should then repeat the text whilst performing an unrelated mimed activity, for instance juggling.

- The actor should be joined by a second actor who should interact with the first, improvising a ‘free invention’ activity while the speech is performed again. Brook is particularly keen on tennis or squash as mimed activities.

Exercise 2: The immediacy of the language

The aim of this exercise is to refine speech through the use of voice recording. ‘The actor's task is not to think of words as part of a text, but&as part of a person who minted them in the heat of the moment.’

Choose an appropriate part of Hamlet and Polonius’ dialogue – throughout the scene the actor playing Polonius uses a device to record the conversation.

Improvise the scene following the dialogue between Claudius and Polonius, integrate the playback into the scene. Does the initial recording make it sound as though ‘the words he (Hamlet) spoke were really his own’?

During follow-up analysis of the improvisation, interrogate the players as Brook does, do we feel him ‘exist, live, breathe and talk’?

Suggest that Hamlet's scripted words are the equivalent of a tape recording, they are ‘a witness that these words were really spoken’. Brook suggests that once an actor understands this, the consequences can go very far’.

Brook's BooksQuotations in this article are from these key sources:

- The Empty Space (1968)

- The Open Door (1993)

- Evoking (and forgetting) Shakespeare (2002)

- Conversations with Peter Brook 1970-2000 (2003)

- The Quality of Mercy (2013)