‘Lend me your ears’: Shakespeare with Key Stage 1 and 2

Maureen Kucharczyk, Stefan Kucharczyk

Sunday, May 1, 2022

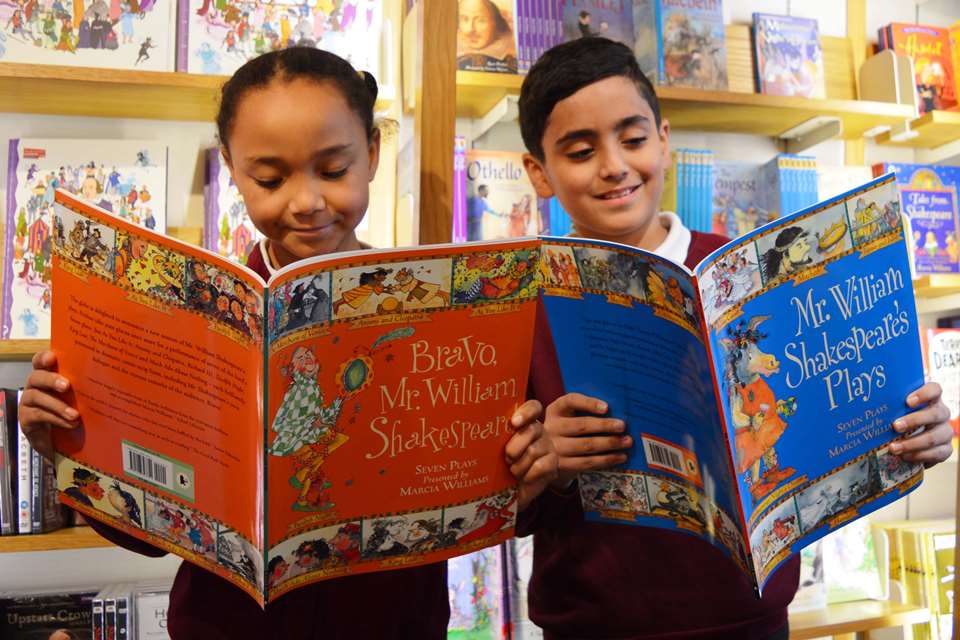

In their new book, Teaching Shakespeare in Primary Schools, Maureen and Stefan Kucharczyk offer guidance and practical ideas for teaching Shakespeare's plays across Key Stage 1 and 2. Here, the duo demonstrate how the plays can engage young readers in an exciting, immersive, fun and relevant way.

Adobe Stock / Mario Breda

We are in no doubt that teaching Shakespeare as part of primary literacy is a challenge. Archaic language, complicated themes and grisly plots may seem to present too great and too mature a challenge for the primary years. Others may find the idea of children studying Macbeth an example of education being out of step with children's interests, how they learn and interact with each other.

In an age where the richness and variety of children's literature is staggering, shouldn't more contemporary and representative authors such as Neil Gaiman, Jasbinder Bilan or Shaun Tan be promoted instead? These are questions we have given serious thought to, both in our teaching of Shakespeare and in the writing of our book. But while the technical challenges are real, none are insurmountable. Such is the ubiquity of Shakespeare in the world that knowing him and his works can only contribute to children's wider cultural appreciation.

A case study: making the film Julia Caesar

Stefan made the film Julia Caesar with a group of Year 4 children as the culmination of a six-part creative writing workshop at a primary school in northern England. He had intended to make a film with the children, but unlike in previous workshops, he made a conscious decision not to decide on the plot for this film in advance but instead to work on the children's responses and draw the ideas from them.

After reading the script for the scene where Caesar is stabbed by the senators, one of the children made the connection that he had been betrayed by some of his friends, notably Brutus. Working on this idea, Stefan asked the children if they had ever felt a similar sense of a friend letting them down, albeit in a less bloodthirsty way! The conversation about what it was like to fall out with friends led Stefan to ask the children if they could think of how this scene might look if it was set in their school and if all the characters were children.

Together, they wrote out some of the key features of Julius Caesar and tried to find parallels in their school life: Caesar was a bit of a show-off, Brutus his best mate who he hangs around with at playtime, the Forum – an ancient meeting place – became the dining room, the prophecy about the Ides of March might come by text message. One boy suggested that the Roman Senate was a bit like their school council where the pupils make decisions about their school.

And that was the lightbulb moment for the group, and we had a loose, parallel plot to work from: Julia Caesar was on the school council with Brutus, Mark Antony and the others. After trying to take over the council, she was finally put in her place by her ‘friends’ who threw food on her in the dinner hall. But rather than leave Caesar dead, Stefan asked the children to think about how the conflict might be resolved peacefully and restore the friendship, which helped us write the final scene together where Caesar and his friends are reconciled with the help of a teacher (and they are all in trouble for throwing the food around).

A unique project

This project was interesting for several reasons, the first being that the children bought into the idea that they had authorial power to play with the storyline, and it gave Stefan pause for thought about to what extent he should pre-determine the direction of his writing workshops. This is the essence of nurturing children's creativity.

The second was that the appearance of the video camera added purpose to the children's rehearsals. This was no longer a literacy lesson; this was a film set, and with their classmates set to watch the film when it was ready, the children actively took on roles as actors, directors and producers with as much seriousness as the role of their character.

Finally, it showed that a 400-year-old play detailing a 2000-year-old political drama still had something to say to children in the 21st century. Like many of Shakespeare's plays, the plots and characters are still around us. With a small mental leap, we can find plenty of points where Shakespeare's world intersects with our own.

You can watch The Rise and Fall of Julia Caesar at www.articulateeducation.co.uk/p/gallery.html

Teaching Shakespeare in Primary Schools is published by Routledge. It contains a wealth of examples like the one printed here, as well as clear advice and practical exercises; and part 2 of the book comprises in-depth schemes of work for The Tempest, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, Macbeth and The Winter's Tale. Until July 2022, readers of D&T can buy the book with a 20% discount, using the code DAT2022 at routledge.com