Practitioner focus: Peter Brook

Thursday, September 1, 2022

Peter Brook, who died aged 97 on 2 July 2022, was one of the most influential international theatre practitioners of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Adobe Stock / C. Willy

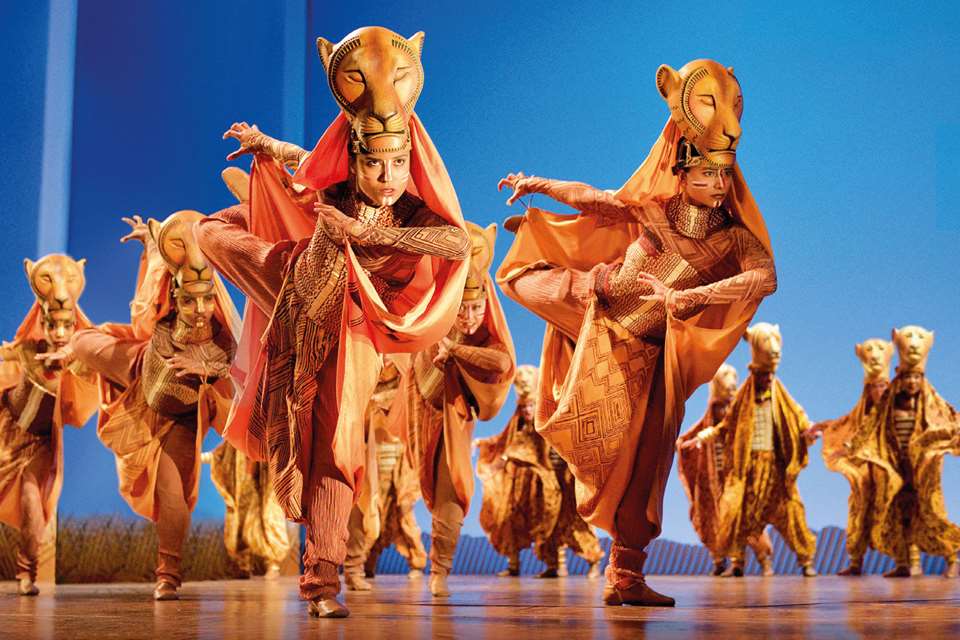

Born in London, he collaborated with some of the most extraordinary figures in 20th-century theatre. His work at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, and then the Royal Shakespeare Company, was confident and revolutionary, culminating in the 1970 production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. It was famously performed in a white box designed by Sally Jacobs, with actors using trapeze and stilts to convey the magic of the play. Two other productions help define his theatrical career, Marat/Sade and The Mahabharata. His move to Paris marked a shift from telling stories with a specific narrative objective to telling stories with overtly universal themes.

Brook's willingness to provoke extends to thoughts on drama theorists, ‘I stayed clear of all theories. I hardly read Stanislvasky or Brecht… I read Artaud… I thought his theories were absolutely useless’. He would not want students to become bogged down in words and theories, but want them to practically explore, examine and act.

To mark his death, we are therefore revisiting some practical exercises inspired by Brook's work and first printed across two issues in 2018-19.

Key influences

Packaging Peter Brook for examination purposes runs contrary to his desire to ‘avoid the snobbery of categorisation’. He is a magpie who believes that ‘life is a patchwork of influences’: Brecht's ideas about theatre as a forum for change and debate influenced the young Brook and Artaud's idea of ‘total theatre’ was another strong influence. Studying Greek theatre and Shakespeare deeply influenced his understanding of the actor/audience relationship and the use of shared space. His work has always had a significant international dimension, and the influence of India, East Asia and Europe (most notably France) can be seen across his work. Brook has said that performance should reflect ‘every aspect of human existence’.

Key features

- The actor is the spring of all creativity

- Actors must always be intensely aware of the audience and that audience must not be passive

- Throughout the rehearsal process it is the director's role to free the actor's impulses, it is a time for rigorous experimentation and for trial and error

- Performance emerges from experi ment ation and shouldn't be pre-planned

- Productions should not be defined by a theatre space; spaces should be designed to suit the play

- Actors must discover simplicity in word and physical action.

Exercises

To match the intentions of Peter Brook, exercises should happen in a space where cushions are provided for non-participants and a marked area on the floor designates the area of activity.

It is important that preparatory exercises are repeated, refined and mined for detail. This process unleashes creativity, making the actor more alive than they are in everyday life (an intention inspired by Artaud). The ensemble is key to Brook's work and his exercises are also designed to create trust and communication between actors.

Mirror Reflection

This simple exercise is repeated throughout Brook's rehearsal notes. Rigorous copying of improvised movement creates a concentration on an actor's physicality.

- Two members of the group focus on an everyday task, one leading and one following through the mirror

- The activity must be watched by the members of the ensemble and then commented on

- The actors then should move with ‘free invention’, once again the activity should be dissected by the ensemble

- Intensive discussion should follow the activity before it is repeated by other members of the ensemble.

Sound in Circle

Brook's works also emphasise sound.

- With the same setup as above, one actor sits in the middle with the other actors sitting on the edges facing outward

- The centre actor makes a sound that is then imitated by the other actors

- The sound is then repeated by the actor in the centre of the group, as the exercise is repeated members of the outer circle supplement the sound. This might be done vocally, or by drumming the floor or percussively hitting the body – creating harmonies and rhythms that liberate the actor from words.

The Tightrope

Perhaps the most famous of all Brook's rehearsal techniques. You can watch him demonstrate it here: youtu.be/EotqLTeLGgs

- Set up the space as above.

- You may lay a rope out as a guideline, removing it before the activity begins.

- The actor needs to cross the carpet as if on a tightrope

- The actor needs to recreate the sense of peril that an actual tightrope-walker has

- The actor needs to recreate the balance that they would need on a tightrope

- The actor should create movements to demonstrate how they are crossing the tightrope.

Discussion: Forensically examine the activity, looking at the sense of peril, the balance and movement, as well as the actor's imagination.

Theatrical journey

Brook's journey took him from ‘using every device known’ on stage to discovering that ‘the human being is richer than the greatest stage effect’. Through putting the human under the microscope Brook unlocked a new exciting world of detail. He believes that ‘acting begins with a tiny inner movement so slight that it is almost completely invisible’, and the director's job is to see the movement and make sense of it for theatrical purpose. This focus has led him to be described as minimalist, yet he firmly rejects this label, ‘I am not a minimalist… I love trying out everything’. His productions became, though, increasingly simplified, concentrating on the relationship between the actor, the audience and the playing space.

© G FREIHALTER/WIKIMEDIA

© G FREIHALTER/WIKIMEDIA

Brook's International Centre for Theatre Research has been based at the Bouffes du Nord theatre since 1974

His view of the director

The director was central to Brook's notion of the creative process and he strongly argued against the idea that directors are unnecessary, ‘without leadership a group cannot reach a coherent result within a given time’. It is the director's job to ‘attack and yield, provoke and withdraw’ and he believed that the director must be in full control in the rehearsal studio. He loved the push and pull between the actor and director that leads to moments of creativity, clarity and discovery. Brook's own notes reveal detailed planning, but he believed that rehearsal should always be fresh, ‘the director who comes knowing what he expects of the actor is a rotten director’. It is helpful to think of Brook as an experimental scientist rather than a ‘traditional’ theatre practitioner.

The audience and the ‘Present Moment’

Given his view of the director it might seem surprising that Brook said ‘too much time in rehearsal can end by destroying the unique possibility which the third element brings’; the ‘third element’ is an audience. If theatre is to be meaningful then Brook believed an audience should engage with the actors well before the play becomes set in stone. He believed in the ‘present moment’, which he compared to an atom that contains infinite possibilities when it is fractured – this analogy reveals Brook's excitement with the explosive possibilities of live theatre.

Shakespeare

Brook's approach to Shakespeare was to try and shed the weight of cultural expectation: a danger he felt could lead to dreariness. He describes his responses to Shakespeare in his book, The Quality of Mercy, but his shorter Evoking (and forgetting!) Shakespeare is a more punchy and pithy text for the student. He is keen to strip the plays of historic baggage, yet also keen to avoid the actors imposing personal experiences on their roles as they develop in the rehearsal room.

Text with Physical Activity

Brook suggests this exercise as way of reinventing text, releasing the word from tired actions. Any piece of text can be selected for experimentation.

- The actor should stand and perform the selected text.

- The actor should then repeat the text while performing an unrelated mimed activity, for instance juggling.

- The actor should be joined by a second actor who should interact with the first, improvising a ‘free invention’ activity while the speech is performed again. Brook is particularly keen on tennis or squash as mimed activities.

The immediacy of the language

The aim of this exercise is to refine speech through the use of voice recording. ‘The actor's task is not to think of words as part of a text, but…as part of a person who minted them in the heat of the moment.’

Choose an appropriate part of Hamlet and Polonius’ dialogue – throughout the scene the actor playing Polonius uses a device to record the conversation.

Improvise the scene following the dialogue between Claudius and Polonius, integrate the playback into the scene. Does the initial recording make it sound as though ‘the words he (Hamlet) spoke were really his own’?

During follow-up analysis of the improvisation, interrogate the players as Brook does, do we feel him ‘exist, live, breathe and talk’?

Suggest that Hamlet's scripted words are the equivalent of a tape recording, they are ‘a witness that these words were really spoken’. Brook suggests that once an actor understands this, the consequences can go very far’.

Brook's booksQuotations in this article are from these key sources:

- The Empty Space (1968)

- The Open Door (1993)

- Evoking (and forgetting) Shakespeare (2002)

- Conversations with Peter Brook 1970-2000 (2003)

- The Quality of Mercy (2013)