The English Actor: From Medieval to Modern

Peter Ackroyd

Wednesday, March 1, 2023

The training, development and landscape for the English actor has changed dramatically over the last century. In an extract from his new book, Peter Ackroyd reflects on the new identity of the English actor.

David Hewitt

What is the state of play and the state of playing? How will the future mould it? Overall, English actors are more persuasive, more accurate and more naturalistic than they were at the end of the last century. They are, to be blunt, ‘better’, although not necessarily greater. This is only partly owing to actors’ training. If anything, they are more influenced by working in a ‘post-Method’ period. It is possible, for example, to conflate styles – even in the same production – that would not normally blend, from the flamboyant to the intimate.

The perennial allure of the actor is now linked with the culture of the celebrity, although this is only a new variation on an ancient theme. For centuries the audience has yearned to resemble the players or to have what they have; they have also wished that the characters on stage might be real, and truly part of the human world. To the fascination of the shaman, or simply of the transformer, is now added the nimbus of fame. This carries with it certain new and perhaps uncovenanted responsibilities. The English actor, for example, seems to be a far more politicized creature than his or her forerunners.

The rise of fringe

Even as provincial rep has declined, the urban fringe has flourished. There are more than fifty fringe venues in London alone. No-one, the actor least of all, expects any remuneration from this, but it is an encouraging development nonetheless. For the actor, it has an added benefit in the frisson of knowing that you are engaged in acting purely for the joy of it.

The actor in the fringe is closer to an Elizabethan counterpart than is the actor in the West End. The pro bono nature of acting in fringe inevitably means, however, that not all can participate, or not for very long. While it can sometimes lead to greater things, the fringe sooner or later proves an expensive indulgence.

Do it yourself

Does any artist have a niche, or their own particular hollow, in history's temple? Perhaps some do, but actors do not. Increasingly, in a world where most are talented and all are skilled, the only gift that makes an actor exceptional is his or her appearance. So it is little wonder that many have decided to take matters into their own hands. Perhaps the most vivid and vital theatre troupe now working, Complicité, was founded, in the words of its artistic director, as ‘a project between a group of people who wanted to work and weren't prepared to wait around and have work given to them’. This leads us to the English actor's current predicament and the solution that many have adopted.

The master theme appears to be autarkeia: do it yourself. You create a company. You form collectives. You write your own plays, direct them and produce them. Everyone participates, in a manner familiar from centuries ago. One young actor observed that ‘when you've created it, you're giving some of that power back to yourself.’ Another expanded on this by remarking that ‘gone are the days of sitting by your phone, waiting for your agent to call: “come on, come on – where's that part at the National?” It's never going to happen. You've got to put yourself out there in whatever way you can.’ All this is heartening. Since the post-war rise of the director, actors have tended to passivity; now, perhaps, they are beginning to remember that they are, after all, artists and not simply hired workers. But there are less encouraging signs, for example the fact that few young actors nowadays want to play in classical theatre.

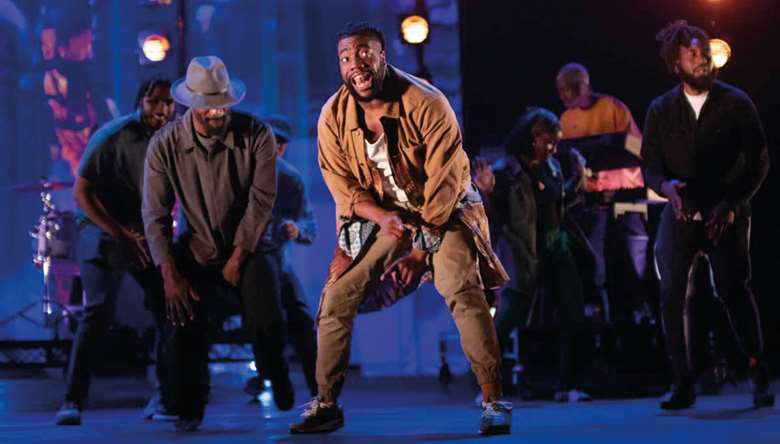

Multidisciplinary work

The actor now lives in a world of many media, and multidisciplinary theatre is one result. There is also devised theatre, in which actors, not necessarily guided by a director, create their own drama. Street theatre can still be seen and may, in time, prove the actor's best hope. But the question cannot be deferred. Will theatre survive in its present state? This question was compounded by the threat of ever-recurring lockdown during the covid-19 pandemic. It may be that, after the great collapse of 2020, a new kind of theatre will be born, one that relies far less on subsidy, a theatre in the open, which is spontaneous and which returns to its ancient roots. Perhaps the English actor will re-mount the pageant waggon and rattle off for the provinces. Or it may be that players will find new and ancient spaces in the crumbling tenement, the stone circle, the disused village pavilion. Come what may, they will once more need their optimism and their recognition that they are part of a tradition that has lasted more than a thousand years.

Peter Ackroyd's The English Actor: From Medieval to Modern is published by Reaktion Books.