Dancing at Lughnasa: Play for study

Nick Smurthwaite

Friday, March 1, 2024

In each issue of D&T we bring you a teacher or academic's guide to a play for study with your students. Here, Nick Smurthwaite introduces Irish text Dancing at Lughnasa

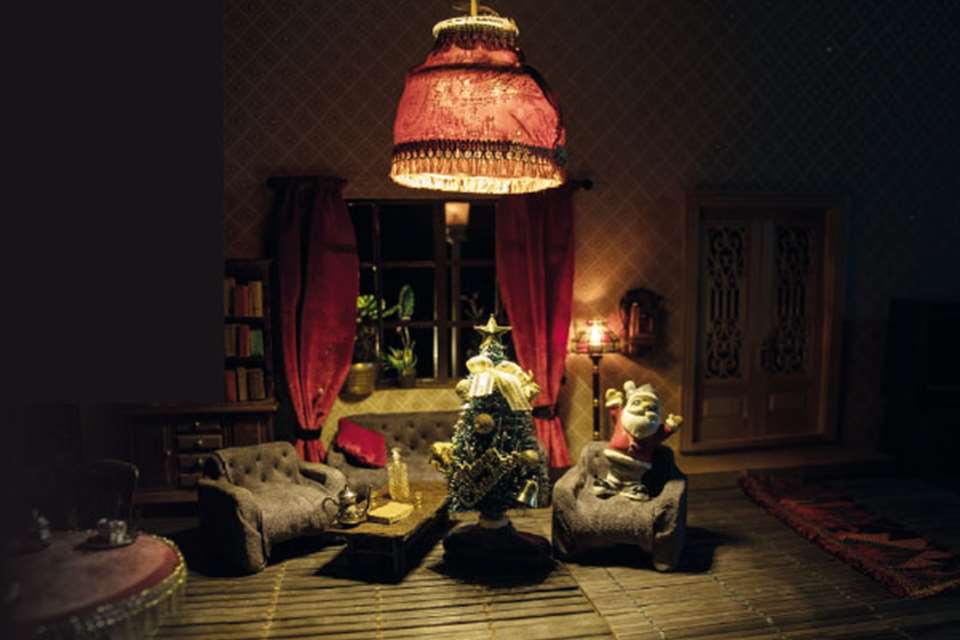

Johan Persson/ National Theatre

Dancing at Lughnasa is one of the most acclaimed plays of the latter half of the twentieth century. Its author Brian Friel (1929-2015) was already known for the plays Faith Healer (1979), Aristocrats (1979) and Translations (1980), but it was Dancing at Lughnasa (1990) that brought him international recognition. A film version, starring Meryl Streep and Michael Gambon, was made in 1998.

The critic Michael Billington, reviewing the play at the National Theatre in 1990, following its transfer from the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, suggested that Friel had become ‘the Irish Chekhov, wresting poetry from everyday life.’

Plot

The narrator, Michael, takes us back to 1936 when he was a seven-year-old child being brought up by his unmarried mother, Chris, and her four Catholic sisters in genteel poverty in the family home in Ballybeg, County Donegal. The Mundy sisters, all single, are trapped and stifled by their economic circumstances. The wider world only impinges on their lives when outsiders enter it. These are their frail older brother Jack, returning from 25 years as a missionary in an African leper colony, where he was accustomed to certain pagan rituals, and Michael's father, Gerry, a dashing dreamer, passing through on his way to fight the fascists in Spain.

The title refers to the nondenominational Irish harvest festival named after Lugh, Celtic god of music and light, who proves to be the catalyst for an unexpected outburst of sisterly joy. Though he was notoriously tight-lipped about his own work, Friel is believed to have based the play on his own childhood recollection of staying with his mother's sisters in rural Ireland in the 1930s.

Themes

In a small rural community such as Ballybeg in the 1930s, the tyranny of faith would have been unavoidable. Teacher Kate, the eldest sister, sets the tone in the household by stamping on anything that might be pleasurable or arousing, and by lionising her elder brother, Father Jack, even though his years abroad have all but purged him of Catholic dogma. Friel constantly reminds you that, beyond the sisters' claustrophobic world of Catholicism and celibacy, exists an alternative world of pagan ritual and fulfilment.

The combination of financial constraints – Kate is the only one of the sisters gainfully employed – and their geographical remoteness makes it difficult for the Mundy sisters to change or improve their situation. Because they choose to be mutually supportive, their lives are bound by domestic routine – baking, knitting, ironing, feeding the hens – and their conversation mostly limited to local gossip and concerns about each other.

However, this does not prevent Friel from introducing social and political issues of the day into his narrative. Among these is the influence of the radio on remote rural communities, so long dependent on word of mouth, and the rise of Eamon de Valera, leader of the Fianna Fail party in the Irish general election of 1933, and the dominant figure in Irish politics for some 30 years. Was Friel hinting at a veiled jibe at de Valera's dreamy vision of rural Ireland ‘whose firesides would be the forums of the wisdom of serene old age’?

The reliability or otherwise of memory is an abiding theme of Friel's work. In his award-winning 1967 play, Philadelphia Here I Come! a young Irishman agonising over his imminent emigration discovers that a moment of remembered childhood bliss – a fishing trip with his father – never actually happened. In Dancing at Lughnasa, Michael's idyllic childhood memories excised the harsh reality of his aunts' shared dilemma – impoverishment, isolation and dependence on each other for survival.

Influences

In common with Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, Friel was extremely loath to analyse his own work or even to talk about himself. Despite often being hailed as Ireland's greatest living playwright, he preferred his work to speak for itself.

A former teacher, short story writer and broadcaster, he was well educated and strongly influenced by the Russian dramatists Chekhov and Turgenev, whose work he frequently translated throughout his career. Like those writers, his work is rooted in the everyday, yet there is always an awareness of political influences and events beyond the control of his characters.

Perhaps his most overtly Chekhovian play is Aristocrats (1979) about a once noble Irish Catholic family living on past glories in a dilapidated mansion in County Donegal they are striving to maintain. It is effectively an homage to Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard.

Another influence identified by Michael Billington, reviewing Dancing at Lughnasa, was Euripides' The Bacchae. ‘Like Euripides, Friel presents us with a conflict between reason and passion,’ wrote the critic.

He was also influenced by other theatre practitioners – he launched his own company, Field Day, with the actor Stephen Rea, in 1980 – such as the directors Tyrone Guthrie and Patrick Mason, as well as the Irish poet Seamus Heaney who was a close friend.

Resources

-

Dancing at Lughnasa, published by Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571144799

-

vinhanley.com/2021/02/06/study-guide-to-dancing-atlughnasa-by-brian-friel/

-

Brian Friel and Ireland's Drama, published by Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0415045744

-

Brian Friel: Theatre and Politics by Anthony Roche, published by Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, ISBN 1349366358