Drama strategy: Teaching history through drama

Patrice Baldwin

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

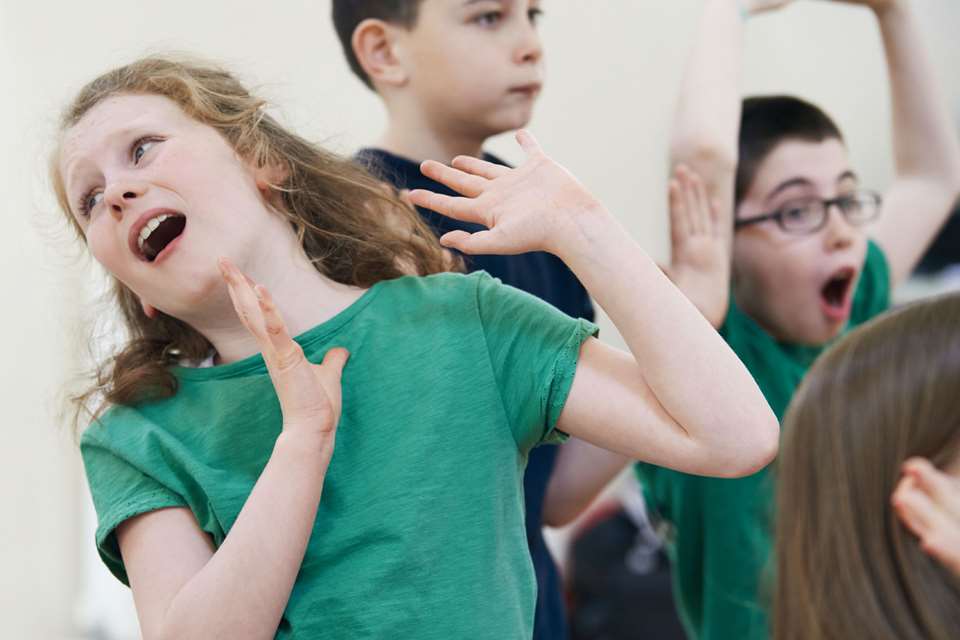

Drama helps children to engage interactively with the past, to re-enact and explore historically significant moments, situations and events, and meet historical characters, (often the teacher in role).

Adobe Stock/ Art Besouro

Hilary Mantel said, ‘good drama does not have to mean bad history’ and certainly, teachers must ensure that a ‘respect for evidence’ is maintained. During historically focussed dramas, children can gain, use and apply knowledge and also develop their conceptual understanding of history, such as change, causation, interpretation. During historical drama lessons, questions often arise, for example: ‘Did the Vikings have glass?’ Teachers may answer such questions or can jot them down, for the children to find the answers afterwards.

History has many films and photographs. Artists too have represented history, in paintings, etchings, tapestries, murals, and so on. Images are a powerful stimulus for drama. Children can be asked to recreate historical images and maybe devise their own. An image can be replicated as a tableau, adding one character or feature at a time and then maybe brought alive through improvisation. Historical images can be studied, then recounted in role, as if by an eye-witness who was present at that moment.

History also has significant texts, such as diaries, manuscripts and letters, which can stimulate drama – for example a teacher can give historical information and answer questions in role as the diarist Samuel Pepys. Also, historically fictitious letters and diary entries can be written during the drama by children working ‘in role’ individually or together.

Individual drama strategies can be used in History lessons but when sequenced within immersive drama lessons, the strategies will help build the drama too. Within an historical drama context, children are invited to engage affectively and cognitively with the subject matter, helping make the learning more meaningful and memorable.

Techniques

Conscience Alley: Children in two lines facing each other. A historical character walks between the lines; each person speaks a character's inner thought as he/she passes by, for example: what might Neville Chamberlain be thinking as he walks towards the microphone, to announce that Britain is now at war with Germany (11:15am, 3 September 1939). This activity could be followed immediately by his announcement, (available online).

Tableau: The class study an historical image, for example Victorian cotton mill workers. They then enter the space in turn, positioning themselves as someone in the image, saying who they are and adding some information, such as: ‘I am the boy under the loom. I am a scavenger collecting bits of cotton that have fallen under the machine.’ (https://londonspulse.org/textile-workers/)

Talking Objects: The class study an image, for example a photograph of the objects in Tutankhamun's tomb, (www.ancient-egypt-online.com/king-tut-tomb-items.html). In turn, they each enter the space, place themselves as an object, stating what they are and adding a piece of authentic information and/or a comment, such as: ‘I am a beautifully decorated throwing stick for King Tutankhamun to hunt birds with in his afterlife’.

Active Storytelling: The teacher tells the historical story, with students spontaneously miming individually in response, such as: ‘It is 1 o’clock in the morning in Pudding Lane. Thomas Farriner is asleep. Downstairs in his bakery, a spark flies from the oven and lands on dry twigs…’ Watch a documentary on the Great Fire of London here: bit.ly/3Cs7LoI

Whoosh!: A standing circle. The teacher tells the story of an historical event, moving along the circle, signalling to individuals/pairs/groups of children in turn, to step forward and mime what is being told at that moment. Once the space gets crowded, the teacher repeatedly calls out, ‘Whoosh!’ and waves his/her arms from side to side, signalling that they should now go back to the circle's edge. The storytelling and re-enactment then continues.

Still Image: Significant moments and events can be presented as a series of still images in chronological order, for example: a dramatized timeline. One example would be before, during and after the Great Fire of London.

Freeze-frame: A moving scene is frozen, giving opportunity for questioning characters (hot-seating) and/or speaking their thoughts aloud (thought-tracking). For example: the moment just before Tutankhamun's tomb is opened.

Mantle of the Expert: Children work ‘in role’ as experts (such as archaeologists, museum curators, anthropologists) with work-related tasks to complete, often commissioned by an external client (teacher in role). The children will need to enquire historically and research before completing the task, for example: to mummify a body in Ancient Egypt during the drama (or teach an apprentice to do so).